PERFORMING PAULINE

(Published in the book "Talking About Pauline Kael: Critics, Filmmakers & Scholars Remember an Icon")

Pauline Kael liked to dial up her friends at all hours, engaging in long conversations. She was both a great talker and -- less well-known -- a great listener. I first spoke to Pauline when she called a mutual friend with whom I happened to be collaborating on some humor pieces. I was living in L.A. and was in his apartment at the time. She asked him to put me on the phone. Pauline and I hit it off right away. We were both Californians, and also Western cowgirls-at-heart who deeply loved the arts.

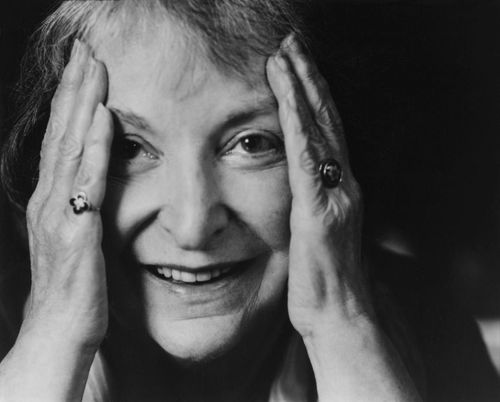

When, in the fall of 1983, I met her in person, she stared up at me. At 6'0", I was a foot taller than Pauline. She gasped, “Oh, my. You have John Wayne legs.” She meant it as a compliment. I think part of why Pauline liked hanging out with me was my height. If ever anyone should have been six feet tall, it was Pauline. She was an Amazon trapped in a tiny spark plug of a grandmother’s body. I always suspected that she felt vicariously tall when we walked together.

Soon I started writing on my own, and she generously gave a humor piece of mine to Daniel Menaker, her former editor at The New Yorker. I owe my first solo sale to Pauline. I soon learned that I wasn't the only writer she'd helped, not by a long shot. Pauline was easily the most generous major writer I’ve ever met. Not only that but her magnanimity was unadorned with the kind of ceremony most celebrated intellectuals demand. If indeed they actually do anything for younger aspirants, it’s usually just to grant them an opportunity to worship. Pauline didn’t simply help writers get published, she loaned money to those who were struggling, handed out lots of advice, picked up checks at restaurants and listened to endless tales of publishing woes. I think she had a deep feeling that an arts person had to give more to the field than she got from it. Only in that way would the arts really have a chance to flourish.

I also learned I was one of the few young writers who became friendly with Pauline without having been a devotee beforehand. Even though I’d loved movies since I was a kid, and despite her public eminence at the time, Pauline wasn’t one the critics I followed regularly. Instead, when I wanted a blast of thinking about the movies I turned to Manny Farber’s criticism in places like Film Comment and Artforum.

So when Pauline and I started talking about movies, she and I often differed. We'd sit at opposite ends of her long sofa in the dark and cozy, high-ceilinged living room of her Victorian house in Great Barrington, Mass., and free-associate. That was another California-ism we shared: a love of meandering conversation. We'd toss around ideas and opinions and let our minds venture onto subjects other than movies.

We'd talk for hours. A recent transplant to New York City, I was hurt the first time someone snapped at me, "Could you just finish one of your damn sentences?" East Coasters seemed to expect speakers to have a point. But, although super-articulate herself, Pauline was very sweet and accepting of my tendency to let my sentences trail off.

She was also more tolerant of my opinions than I was of hers. I had a hard time forgiving her for not loving one of my favorite films, George Axelrod’s satire about Southern California and ‘60s teen beach movies, “Lord Love a Duck.” I loved “Dirty Harry” and Clint Eastwood in it; I was a fan of early Werner Herzog and Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Pauline would mutter “Oh, oh, oh” when I raved about some film or performer she couldn’t stand. Sometimes she’d give me an impatient “Oh, honey!” and roll her eyes. Particularly hard for her to understand was why I saw profundity in the Technicolor melodramas of Douglas Sirk. She really peered at me through those big eyeglasses of hers over that one. Most of the time, though, she drew me out and was eager to hear why I liked something she didn’t. She'd never talk about it, but one thing Pauline radiated was a conviction that being a writer isn't just about carefully crafting your words. It's about being part of -- and contributing to -- the artistic community. And Pauline, contrary to the impression some people had of her, would never have wanted everyone in the artistic community to agree with her.

As we talked in the winter, snow and ice would pile up outside her house. In the summer, mosquitos would hover outside her screen door as evening approached. The sun would set and she'd say, "Pol, would you mind turning on a little light?" I'd get up and switch on one of her Tiffany lamps. "That's nice," she'd happily murmur. Pauline didn't just have strong reactions to films: she reacted fully to what each moment brought her. ("Ghastly" was one of her favorite things to utter when she didn't like something or someone.) Then we'd talk some more.

***

Early on in our friendship, Pauline introduced me to Ray Sawhill, one of her favorite young writers; within a few years Ray and I got married. (Pauline often claimed, with a mischievous smile, that matchmaking our marriage was one of her proudest achievements.) I’ve sometimes suspected that a major reason she paired us up was that I didn’t object to the amount of time the two of them spent talking to each other. Ray and Pauline yakked for hours, and nearly every day. Many wives and girlfriends were jealous of the attachment their men felt towards Pauline, but not me. I was relieved that Pauline and Ray had each other to gas on with.

The three of us spent many a New York City evening seeing a movie or two and then going to dinner afterwards at one of the restaurants she favored: Cafe Un Deux Trois, a Japanese restaurant where she always ordered the eggplant, or the branch of Fiorella's on the Upper East Side. Pauline always brought a collection of herbal teas with her in a small plastic bag. Despite all the time Pauline had spent living in the northeast, and despite her extreme sensitivity to the heat, the humidity and the cold -- it always seemed as though the northeast weather was really torturing her -- she never abandoned her NorCal habits of dress. She never learned how to dress for the cold, for example. When she and I would visit Bloomingdale’s together I’d steer her towards the sensible, heavy coats, but she inevitably wound up buying yet another pale colored, lightweight quilted kimono jacket.

Ray and I spent dozens of weekends with Pauline at her house in the Berkshires. The guest bedrooms on the third floor were painted in shades of blue and yellow that reminded me of the palette of her artist friend Jess -- Art-Nouveau-meets-1950s-San-Francisco colors. The bathrooms didn’t have showers, just ancient claw-footed bathtubs. In the alcove off her living room was an old upright piano that Jess had decorated and a huge bookshelf full of books about the movies. Tucked under tables all around the house were stacks of screenplays and manuscripts filmmakers, screenwriters and novelists had sent her, wanting her feedback. The place had an airy and spacious feeling, a mix of old wood, fresh sheets, magazines and books, the bouquets of flowers that she adored and the chunky tomato sauce that was almost always simmering on her stove. It expressed such a Northern California aesthetic that I kept expecting to see the Golden Gate Bridge every time I looked out one of her windows.

In the mornings, as Ray slept late up on the third floor, Pauline and I would idle away a few hours in her kitchen. She’d pad around, heating up bread and tending to her beloved windowsill violets. She’d put out a spread of cheeses and fruit, and bread from a local bakery. If we were lucky, the critic Steve Vineberg would have been by and dropped off one of his delicious braided Challah loaves. Some mornings I’d make a quick run into town and return with The New York Times that the local news store always kept for her.

We’d sit side-by-side on high stools at her butcher block table. She was a wonderful cook who didn’t need high-tech gadgetry. The stove seemed to be from the 1950s, the sinks from the 1910s. She didn’t own a microwave, a Cuisinart or an automatic dishwasher. She always had a stack of magazines and clippings in the kitchen that she was eager to gab about. Many of these pieces were by friends and acquaintances. Pauline kept up with just about all her friends’ published writing, theater productions, screenplays and shows of their art. It didn’t matter how small the magazine was or how obscure the gallery. If you were her friend, she wanted to see, read or hear what you’d created -- and then weigh in, whether you wanted her to or not.

We’d pass our mornings in an easygoing burble of gossip, food and reading -- punctuated by Pauline saying one of her pet phrases with a laugh, “It’s a funny world.” We’d share nostalgic memories of California and the casual egalitarianism of life there. She'd rave about something her young grandson Will Friedman had recently done. Will and I got along famously and Pauline liked that. We’d pause to “ooh” and “aah” about the goat cheeses she had on hand. She always proffered a sweet little vintage China plate with three or four lumps of cheese on it. Pauline could be famously tough on movies but I don’t believe she ever met a goat cheese she didn’t adore.

Despite all the reading and gossip, our morning conversations always came back to food. Both of us were deeply interested in the topic. Not that we didn’t differ about food as much as we did about movies. (We did overlap on the goat-cheese question, though.) I thought the low-fat vegetarian diet she followed -- she hoped it would help her troublesome heart thrive -- was dumb. In turn, she'd sigh over the rich French food I preferred to cook and eat. “Oh, Pol,” she’d murmur with disapproval. “That’s killer cuisine.” Then we’d giggle. I’d sip my latte, she’d sip her herbal tea. During the years I knew Pauline, I never saw her consume anything caffeinated. Then we’d start to plan out what we’d have for lunch and dinner.

***

I loved hanging out with such a brilliant and charmingly intractable personality. Even so, there was one area where there was tension between us. It had to do with my development as a creative person and my own career as a writer. Pauline may have been OK with me differing from her in my movie tastes but she dearly wanted me to become a critic.

Not that that made me super-special. Pauline wanted nearly every young writer she liked and had hopes for to write criticism. It was her chicken-soup solution for any bit of confusion any of her young friends ever expressed to her. A number of the young writers who genuinely wanted to be critics embraced her advice and accepted her help, and then, almost inevitably, went through some Freudian drama of rejecting her, often in public. I found these dramas unfortunate. How could people who owed so much to her inflict this on her later? But she seemed to accept their acting-out-in-public as a kind of inevitability.

I found it flattering that Pauline would want me to write criticism. Imagine having one of the greatest critics of all time insisting that you had it in you to become a great critic too. But I also found her fixation odd. I was young and unformed; god knows I was in need of guidance; and people seem to enjoy talking to me about the arts. But one thing I knew for certain was that my interests where my own writing went tended in the direction of humor, fiction and theater. Why would she not pick up who I really was?

At first, I’d try to explain what I was looking for to Pauline. “Oh, Pol,” she’d murmur, taking out one of the little lozenges she was always treating herself to, especially when she was disgusted with what you were trying to say. “Virginia Woolf and Graham Greene both did criticism as well as fiction. It was good enough for them. But not you?” She was a virtuoso at the blindside nudge. Then she’d peer at me accusingly through her big glasses with a mixture of disgust and disbelief, as though I was failing completely to see the light. When I tried to evade her she’d track me down. She’d have been one hell of a lawyer.

And all right, all right -- at one point I did give in. How could I not? Pauline was so smart, so encouraging and so warm, but she was such an unrelenting bulldozer too. In the early '90s, when I was doing a lot of journalism for glossy magazines, a woman's magazine asked me to take over their movie reviewing. So, for a stretch, first at Harper’s Bazaar and then at Elle, I played the professional movie-reviewer game: going to screenings, scrapping with p-r people, dueling with editors over space and which movies to cover, and ginning up enthusiasm about movies I didn't really care much about. (Can you tell it wasn't for me?)

Pauline was thrilled. Suddenly I was doing what she thought I should be doing. She badgered me to see all my copy before I published it. I resisted every time -- every time except once, when I was trying to capture what I had loved so much about the Andre Gregory/Louis Malle film "Vanya on 42nd Street." Her editing suggestions were brilliant and helpful on that review, and she didn’t try to impose her voice or to change my reaction to the film.

As pleased as I am with some of the writing I did during that stretch, I loathed being a critic. The paychecks and deadlines were OK with me; what I mainly disliked was panning people and telling the world what they’d done wrong. It’s a question of temperament. Even when I dislike an art or entertainment thing, I’m always prone to thinking about how hard the artist has worked, and how many hopes he or she has that it will please people. Nobody tries to make a bad work of art. And anyway, are artists, even bad artists, causing wars or bringing down financial systems? I don’t think so. So why not try to see what they’ve done in a positive light?

Needless to say, Pauline thought my attitude made me a wuss. She liked artists too, but in her worldview, artists -- and audiences too -- really had to have her opinions and reactions, both positive and negative. She was driven by a deep, genuine feeling that the world needed to hear what she thought and felt. “Pauline,” I’d say. “I just don’t think my opinions and reactions to movies are of that much importance.” She’d give me a disgusted "Oh..." and change the subject.

After two years of reviewing I was miserable. I’d set aside too many of my own creative projects; when movie people called or wrote to complain about my reviews, I’d agree with them and apologize. One day in yoga class, a woman came up to me while I was doing Downward Dog and told me that a negative review I'd written of a movie a friend of hers had made had hurt that friend deeply. I felt so badly that I toppled out of the pose. I even developed a whopping case of carpal tunnel syndrome. I was ecstatic the day my review column got cancelled at Elle, and in the years since I've never written another piece of criticism or pursued another reviewing position.

My decision to abandon criticism really bugged Pauline. She thought that my getting fired was a sign I should redouble my efforts. That was not in the cards, to put it mildly. I needed to find my own way of being a writer. But how was I to maintain my friendship with Pauline even as I went my own way? Would it even be possible? I tried to bond with her by talking about fiction. But she didn’t like the novelists and short story writers who’d had the biggest impact on me, popular-fiction authors like Ira Levin and Jacqueline Susann. Instead, she’d push a copy of The New Yorker at me, folded open to a story by someone like Alice Munro or Allegra Goodman and she'd tell me she thought these writers were “really getting at something.” I'd try to explain that I had no feeling for this kind of contemporary literary fiction and that I couldn’t get through more than a few paragraphs of their stories. More peering at me through those big glasses. More taking out of throat lozenges.

The time had come to put up a wall between us, and I did. It was the mid-‘90s by now and she’d retired. Ray continued with his routine of daily phone calls with Pauline and once-a-month weekends with her in Great Barrington. I didn’t accompany him. Pauline and I were occasionally in touch by phone, but I began keeping my writing and my goals to myself.

It was more than a little awkward. Pauline hadn’t been able to influence or mold me the way she’d wanted to, and she couldn't resist letting me know her disappointment about that. Meanwhile, she could see that I was floundering as I tried to make my own way: writing articles about food (surprise); doing schlocky, pay-the-bills celebrity journalism; and starting to work on theatrical projects. The floundering caused me anxiety, but I persisted; I needed to figure out where to take my writing next, and I needed to do that under my own steam.

After a few years, I felt I’d sufficiently found my own footing. I no longer needed to have that wall between us. That snowy January I made a trip up to Great Barrington by myself. I walked up the stairs and into her kitchen, where the tomato sauce was bubbling on the stove, and I nearly burst into tears because I’d missed Pauline and that memory-laden house so much. I was glad I’d kept my dark glasses on. Pauline wasn’t one for sentimentality, let alone discussing relationships, or apologizing, or hashing things out. She just brought out a plate of cheeses. “This new goat cheese is quite yummy, Pol. You must try it.”

I feel very lucky that our rapprochement happened before she died. We don’t always get that kind of chance. Pauline and I went back to hanging out in her kitchen, gossiping, reading, and going out to restaurants in town. In those final five years, as her heart problems and Parkinson's Disease knocked her down over and over again, I was fortunate to be one of the people who spent a lot of time helping out and taking care of her.

***

In the decade following Pauline’s death in 2001, I often missed her. Ray and I both found it a strange and empty feeling not having her as a constant presence in our lives. When the phone would ring, I’d pick it up expecting to hear her say, “Hi Pol, I’d love to get both your and Ray’s takes on Maureen Dowd’s latest column. I think she’s really onto something.” I’d be in certain restaurants and think: "Now this is a place that Pauline would have loved!" I’d pass the photos we have of her in our apartment and feel pangs of loss. How quickly she seemed to be receding from our lives.

They were pangs not just for my own sake but for how quickly she seemed to be receding as well from the culture. 9/11 happened just days after she died and took the country in a whole new direction, towards the security state and constant inroads on civil liberties. (Pauline had often expressed her feeling that G. W. Bush would be a disaster.) And would Pauline have been as stalwart a defender of Obama as she’d been of Clinton?

I started meeting young film buffs who’d never heard of her. At first that was impossible for me to believe. A few years later, the opposite would be true: when I ran into a young film buff who actually did know who she was, I found that even harder to believe. It was strange to see how movies from the Pauline era didn’t matter much to the young filmmakers and screenwriters we were meeting. Many of them hadn’t seen Robert Altman’s “Nashville” or Bernardo Bertolucci’s “Last Tango in Paris.” The ‘70s movies our young movie friends wanted to talk about instead were films that Pauline had either not been interested in, or had been barely aware of: Italian giallo thrillers, Japanese “Pink” films and horror movies like “The Last House on the Left.”

And then there was the internet. Ray and I both have memories of Pauline standing in front of a Mac with a baffled smile of incomprehension. She was notoriously terrible with machines. Yet she loved it during the ‘90s when friends gave her printouts of articles that had appeared online. But how would she have felt about the internet disrupting and displacing the world of print magazines and books in which she had flourished? A lot of the magazines Pauline loved subscribing to started having terrible business problems. Pauline had always felt that part of her duty was to battle the gate-keepers. In the years since her death, I've often found myself wondering: what would Pauline have made of a world without gatekeepers, a world in which anyone with a computer could hit a button and publish him/herself? Who needed to hire, let alone pay, a movie critic when everyone now had a megaphone? I watched sympathetically as a number of writer friends had breakdowns, gave up, or just became depressed and angry at the way the media world was evolving.

Ray was released entirely by the arrival of the web; he created and co-wrote a popular culture blog, 2Blowhards. (He'd never enjoyed doing professional writing anyway.) As for me, though I began running my own website in 2002, I've never had a love affair with the internet. Still its arrival released me in a different way, and in all kinds of directions. I wrote a collection of erotic-horror short stories called “Deep Inside” and published them traditionally. I did some self-publishing.

With Ray and a talented young filmmaker named Matt Lambert, I produced a webseries, “The Fold,” which we like to describe as “Barbarella” meets “The Matrix” and the 3 Stooges. It's a loopy, sexy underground comedy for the web age. (Matt, a brilliant director out of NYU, had barely heard of Pauline Kael.) We tried to get some of the movie reviewers we’d known through Pauline to look at "The Fold," but most of them weren’t interested in looking at a webseries. The only movie critic who gave it a look was David Chute, who hadn’t been a member of Pauline’s circle. David was kind, and enthusiastic enough to compare “The Fold” to early Almodovar. Because of all these activities, for a few years I became a bit of a new-media personality. I was being interviewed; I was asked to be on new-media panels and to go to cyber conferences.

Despite these adventures, my strongest instincts ran in the direction of live performance. In an age of infinite reproduceability, maybe what would mean most to people would be live appearances. So I dragged Ray into collaborating with me on a theater project entitled “Sex Scenes,” an ongoing series of X-rated satires set in the moviemaking world; we put on episodes monthly at Greenwich Village’s Cornelia Street Cafe, using terrific New York actors who read our scripts as though they were radio plays. Putting these shows on, I began learning things I’d never known how to do before: how to meet and work with actors, how to line up a venue, how to attract attention without going broke buying ad space, how to emcee shows.

If a young Pauline were coming along in these new days, would she have been a movie reviewer at all? Pauline was becoming less and less of a presence in the culture, and less and less of a presence in my own brain. I had looked for her so often in that decade since her death, but eventually I knew she was gone. I even stopped having conversations with her in my mind. One day I was passing through our apartment and realized that the large black and white photograph of her that we have on our living room wall was fading from the bright sunlight that streams through our south facing window. It's a window that once looked directly out at the World Trade Center. I moved the photo into a shadowy spot, wondering as I did what her legacy was. Was there going to be any legacy at all?

***

In 2011, I wrote “How to Survive Your Adult Relationship With Your Family,” my first one-woman show. After a decade of experimenting in the new media world, and after thousands of hours of sitting in front of computers, what I'd come to feel I really wanted to do was connect with the oral tradition that existed not just before the internet but before print entirely. I performed the show in more than a dozen cities across the country. In 2012 I wrote and began performing my second show, “Bad Role Models And What I Learned From Them.” (Not to worry: though she makes a brief appearance in the show, Pauline isn’t one of the bad role models.)

By a strange twist of fate, my turn to live performing coincided with the publication of Brian Kellow’s excellent biography, “Pauline Kael: A Life in the Dark,” and the publication in the prestigious Library of America of Sanford Schwartz’s "The Age of Movies: Selected Writings of Pauline Kael." Suddenly Pauline was rediscovered. She was back in the news, even back on the front page of her beloved New York Times Book Review. Lo and behold, Pauline Kael was still a cultural figure about whom people had strong opinions. Ray and I were among the sources for the biography and we’ve become friends with Brian Kellow since. We appeared with Brian once at the 92nd St. Y in Tribeca, and it was heartening to see how many people still felt an intense engagement with her work.

What with the books' publication and my turn to live performing, my inner connection with Pauline has been rekindled. In my one-person shows I’m sharing ideas, reflections on art, personal observations and stories. I’m throwing just about everything I’ve thought, felt and experienced into them. Pauline is a great inspiration for that. After all, she didn’t just evaluate movies in her reviews. They were vehicles for her entire being, for everything she'd come to believe and think about the world. She brought a number of disciplines and fields she knew a lot about to her criticism. She knew philosophy and sociology, she knew architecture and design. She hung out with Bay Area poets and painters of the Beat Era. She’d run a salon at her house in Berkeley and knew how to play hostess to a crowd; it always seemed to me that her writing reflected her experience as a party-giver.

I’m going to venture a thought that some Pauline fans may find hard to assimilate: she wasn’t just one of the greatest critics, she was also one of the greatest performance artists. That may seem like a strange assertion to some people who see her only as a reviewer, but one of the most striking things about her writing is its dramatic urgency. Each of her columns is as arced as a play or a movie. If you take any one of Pauline’s reviews and read it aloud, you’ll see how beautifully it works as a performance piece.

Which makes sense. As a critic, she started out reading her reviews on the Bay Area station KPFA. And that background in radio stayed with her, I think. Pauline, much more than other writers, saw her columns as oral performances. She read her reviews aloud to friends and editors as she honed them. (From the early ‘80s until she retired, she read many of her drafts to my husband before bringing them to her New Yorker editors.) This performing and revising, performing and revising, was her creative method. And for a reason: She never wanted her readers to feel as though she wasn’t talking directly to them. She was very tuned into her listeners’ responses, and she deepened and elaborated her pieces as she tested them on friends and editors just the way that theater people do workshops of plays in front of friends and colleagues before mounting productions.

It’s seldom appreciated too how much of a jazz buff she was. She’d often talk to us about what jazz meant to her as a writer. (She loved opera as well, but I can’t remember her talking about opera being an influence on her approach to writing.) She liked the way jazz performers improvised on top of solid structures, and she loved the way they took you along for a ride. Above all she didn’t want anything to sound canned. Her reviews show her love of that music: she varies the tempi, she has fun with her themes, she goes off on long riffs. She once said to Ray and me in a q&a we published in Interview magazine, “I want what I do to move along by hidden themes. I rarely try to think anything out ahead of time. I want it, paragraph by paragraph through the whole structure, to surprise me. I want the fun of writing. I don't want to take the juice out of that.”

And let’s not forget that when she started out as a young writer, she wanted to be a playwright. She once gave Ray and me some of her early plays to read. I could sense the brainy, vervy -- (boy, is that word “vervy” a Kaelism or what?) -- talent behind the writing, and she certainly displayed real playwriting skills so far as structure went. However, I could also feel that Pauline’s heart wasn’t in creating fictional characters for the stage. It was as though she couldn’t give over to the characters she created, or even let them say what they believed.

When we returned her manuscripts to her, I was apprehensive about telling Pauline what I thought of her plays, but she insisted I do so.

“They seem a little constrained to me,” I said.

“What do you mean?”

“I sense you wanting to tell your characters what they really should be doing," I finally said. “You seem kind of annoyed with them.”

“Oh, oh, oh," she whimpered, looking a little dismayed and popping a lozenge. Then she brightened and said, "That sounds about right." She knew deep down that creating characters and fictional worlds wasn’t her métier.

***

Still, if Pauline knew about anything, it was performing. Among writers for the page, she was unusual -- an extrovert who embraced performance. The real-life Pauline saw herself both as an intellectual weighing in on culture and as an entertainer with a regular gig and a connection to an audience. She was, along with everything else, a trouper who never wanted to let her readers down. In her criticism she laid far more emphasis on the power and allure of performers than most intellectuals writing about the movies do. She may have had very little drive to create fictional worlds and characters other-than-herself. But she had a powerful drive to play herself and to discuss the real world around us through her persona.

But that persona was, in fact, a creation. I don't think this has been emphasized enough in discussions about her. I've found that many people, discussing Pauline Kael, the writer and public figure, seem to think they're also discussing Pauline Kael, the real person. It's not a mistake sophisticated people like Pauline's fans are generally prone to, but in this case it's common.

I can understand why. The character she played in her reviewing wasn't one of those branded characters we're all familiar with: Jackie Gleason, with his “and away we go”; Tom Wolfe with his sartorial dandyism; Jack Benny with his way of folding his arms. Pauline’s portrayal of "Pauline Kael," by contrast, always looked natural. She seemed very spontaneous and schtick-free. She didn't dress up, either for TV appearances or in her prose on the page. There was never anything that seemed processed or pre-packaged about her writing or appearances. She comes across instead as a very real personality, leaping off the page, out of the TV. She always seemed to be speaking directly ... to you. Small wonder that so many people carried on conversations with "Pauline" in their heads in a way they didn't with many other public personalities.

This "Pauline" overlapped a lot with the real Pauline Kael, but there were sides of the real Pauline that didn't show up much in the public "Pauline." Some examples: Given the exuberant, barreling-ever-forward quality of her published prose, her physical fragility often took me by surprise. The first time I walked around New York City with her I thought she’d own the sidewalk. Instead she was physically very vulnerable, covering her mouth with her scarf to protect against cold and grit, shrinking from the aggressive and fast-moving crowds, and reaching for my arm to steady herself. She had tissue-paper skin that flushed a lot more than I expected. Given Pauline's public persona, I imagined she would dominate any dinner table -- but for someone who came across as a diva in print she could be surprisingly deferential in real life towards other people and gave them plenty of room to speak. Many people were surprised by Pauline's speaking voice. Given the ferocity of her New Yorker columns, you'd have expected her to sound like a growling, gruff Bea Arthur. But in in-person conversation, Pauline wasn't a belter, she was a wafter. Her sentences were breezes on which brilliant ideas and observations floated. Of course, sometimes those breezes of hers carried enough acerbic punch to knock you down.

The Pauline Kael she played in her reviews came out of the gate with hurricane-force opinions, but the Pauline Kael I knew was more prone to stewing and noodling. She gnawed away at the movies she’d seen, she gnawed at how her friends behaved, she gnawed over the sentences she was composing for her reviews. She gnawed and wouldn't let go until she broke through to the essence of something and understood it.

Going into this phase of my own career, I didn't know in advance that learning how to perform myself would be the hyper-important creative issue it's turned out to be. To the extent that I thought about it all, I believed that playing myself and speaking in my own voice would be easy and natural. In fact it's been a major creative challenge. The character you play has to to be something you can move into easily and directly -- otherwise you'd never be able to play yourself night after night. But it also has to be something that isn't quite the real you, because you need some protection as well as a little creative distance and control over what you're projecting. Besides, you only have the one evening to make your impact, so you need to move quickly. To use my own performances as an example: onstage I play up my spacey California side for comic effect. Also, while in real life I can often be shy and insecure, onstage I try to project confidence even as I talk about times in my life when I've lacked it. The trick is to turn yourself into a bit of a caricature -- yet one that's also a living, breathing three-dimensional person.

The years I've spent developing my performance as "Polly Frost" have given me a new appreciation for Pauline's achievement. Pauline Kael may have failed at being a playwright, but she went on to create "Pauline Kael," one of the most resonant characters in American literature, theater or the movies. Pauline Kael is an explorer in the world of aesthetics who can not only share tips and responses but can entice the reader into brilliant, labyrinthine Henry James-like sentences that take Beat poetry turns and finish on the stand-up comedy stage. She's as good as Friedrich Nietzsche at exploding widely-accepted notions in a single sentence. She's a heroine who promises to take Americans through the heart of our puritanical darkness and into an incandescent red-light district where pop culture and high culture bring out the best in each other. In her reviews Pauline is a feisty cowgirl who doesn’t have any truck with those Americans who bow down before European culture, yet she can hold her own with any scholar when talking about the cultural canon. She can rave about the Ritz Brothers but also swoon for a filmmaker like Jean Renoir with his Old World poetry. She's a no-nonsense wisecracking dame out of a dialogue comedy, yet one whose jokes always deepen the discussion.

***

There's another dimension of my new life as a performer that has brought me into intense conversation with Pauline: It's almost as though the two of us are back sitting on opposite ends of her couch having one of those long conversations we used to have. It has to do with what kind of relationship to cultivate with audiences.

When I began performing, I was disconcerted. After nearly all my performances, audience members would come up to me and introduce themselves. Then they'd want to talk to me about their own lives. At first I found this very unsettling and I'm afraid that, I didn't handle it well. Exhausted from having just given a ninety-minute performance, I’d think, "Why are these people demanding more from me? Can’t they just tell me how much they loved me and go away?" My perplexity was compounded by how personal my shows are. I felt intensely vulnerable. At the same time I felt bad about not meeting their eagerness to connect with some friendliness and appreciation of my own.

I recognized that, as proud as I was of the show itself, this was a problem I needed to wrestle with. What would Pauline have to say about how to handle the situation?

If ever there was a writer who wrote for, loved and was inspired by her audience, it was Pauline. A lot of writers, bless their hearts, are very private people. Pauline, by contrast, wrote for and wanted to connect with a sizable public. In fact, I don't know that she would written at all had it not been for the chance to connect. She liked meeting people in public. She loved speaking to large auditoriums full of people. She maintained a huge ongoing correspondence with her fans and followers. Her dining room table always had a six inch deep stack of letters she'd received, and it was one of her writerly joys to sit down and tend to it. Aside from psychos and whackos, she wrote back -- often a short note but sometimes a sizable letter -- to nearly everyone who wrote her. I know people who received responses from Pauline who've treasured them their entire life. She created reactions in her readers and then absorbed and was inspired by the energy they gave back to her.

It has seemed to me that one of the most pressing questions for any performer is the issue of "likability." The writing -- and especially the intellectual set -- generally chortles when topics like this one come up, but all performers know how central they are to the performing arts. How do you win your audience over? Using what qualities in yourself?

Where these questions go, Pauline was an interesting case. She lived to tweak and provoke. She was nothing if not challenging, and she had a deep dislike for artists who pursue being liked or admired too directly. She was irritated by Tom Cruise’s desire to be endlessly likable and she groaned over Meryl Streep’s Vassar-valedictorian respectability. She preferred Marlon Brando’s brutality and Debra Winger’s messiness.

Some critics have an aesthetic that they promote in their writing, but not in their life. With Pauline, the aesthetic she believe in went to the core of her own being. Take her review of Martin Ritt's 1963 “Hud." At one point she writes: “Rape is a strong word when a man knows that a woman wants him but won’t accept him unless he commits himself emotionally. Alma’s mixture of provocative camaraderie plus reservations invites ‘rape’.” Strong stuff. If she wrote that passage today, would it even be published? And if it were published, what kind of hatefest would it set off? Over and over, Pauline went after complacent, self-congratulatory beliefs. She’d zing feminists, gay activists, right-wingers and left-wingers alike. She knew that part of the primal power of movies is that they take us to places we intellectually think we shouldn’t go, yet we can’t resist.

Despite what some people saw as perversity and aggression, many other people went back to her reviews week after week. What drew them? It was partly her mischief, partly her piercing intelligence, partly her depth, partly her zeal as an educator, and partly her spirit. She was also a great journalist and observer of life; she was illuminating about the world around us. But maybe above all it was her honesty. She was nothing if not, always and everywhere, true to her own feelings and muse. How to resist somebody who was so fully, unapologetically, exuberantly herself? Her brattiness, even her rudeness, became endearing.

Maybe part of it as well was that she was championing an under-appreciated form. Hard to imagine in these days, with pop culture and glitzy technology running rampant and traditional culture on the defensive, but at the time she wrote she was making a case for a popular form that a lot of people had a great fondness for but had intellectual misgivings about too. In a sense, she was on the side of the underdog and was making us feel good about being Americans, and showing how to do so without being some flag-waving patriot or cultural rube.

She alternated between appalling her audience and winning them back. She antagonized them, and then cracked them up. She pushed their buttons, then she seduced them. It seems to me that that's a big part of where the "dramatically effective" -- in other words, galvanizing -- quality in her work comes from. She's always putting you off then winning you back. It's that dramatic force that gives her portrayal of "Pauline Kael" much of its power. It may be the main reason why many of her readers carried on conversations with her in their heads for days after a review of hers was published. I knew people who had carried on conversations with Pauline in their heads for years. (She'd show me the passionate, furious letters they’d write her.) Tom Cruise needs his audience to like him. Pauline, by contrast, liked her audience and liked performing for them, and that's where much of her own likability came from.

Then there's the question of actually dealing with audiences. It's the very practical question of how to manage your direct, in-person contacts with them. Before my first performances I needed a good half hour in the green room to focus, away from everybody. I don't have the stage nerves many people do. I find performing very enjoyable but I needed to pull my energies together and get my feelings in order. I wanted to go out on stage, right at the outset, like a ball of entertainment energy. Then, after the show was over, I would be completely drained. When people who'd watched me came up afterwards and wanted to talk to me, I'd be prickly. Not good. What did Pauline have to suggest to me on a practical level?

Pauline enjoyed writing, and enjoyed time by herself, but she was much more extraverted than most writers are. When I was out with Pauline, people would often come up to her and start arguing with her about a recent review. She was never put off by their advances. Pauline knew she had that effect on people. She wanted her writing to have a vividness equal to the best movies. I don't think I'm the first to say that her reviews were often more powerful than the films she wrote about. Reading her, fans created their own movies in their heads. That’s been a huge influence on my own performances. In my own way I’ve tried to create shows that take on a movie-like quality in my audience's minds. It's just me up there, alone on stage. But I want my audiences to leave the show feeling that they've experienced something as big, as heightened and as emotional as a movie.

In my mind I could hear Pauline telling me that if I was going to enter into that intense a relationship with my audience, then I had better be willing to deal with the consequences of it. So now I've changed my approach to the people-surrounding-a-performance factor entirely. Before a show I no longer hurry to the green room to sit by myself. Instead I mingle, both with the theater staff and the arriving audience members. At the end of my shows I now announce that I'll be sticking around for a half an hour and would love to meet people. I'm deliberately smudging the lines of where a show can be said to start and end. What I'm looking for these days is for people to feel a little less that they're here to see a show in a conventional sense and more that they're just spending some time with me. (Then -- blam! -- I can hit them with my jokes, observations and emotions.) As I've opened myself to this way of running an evening, I've found myself really enjoying a lot of these pre- and post-show moments. A few of the people who have introduced themselves to me me after my shows have become real-life friends.

***

I suspect that one of the reasons Ray and I (and a few others) became as close to Pauline as we did was that, even during her peak years, we understood that there was a distinction between the public and private Pauline Kael. It was one of the reasons we grew even closer to her during her decline too. She'd created one of the great characters of our age and given one of the era's great performances, but in her final years she didn't want to bother turning it on any longer. Performing "Pauline Kael" would demand energy and confidence that her Parkinson’s Disease was taking away from her. I had loved being around the “Pauline Kael” she played with such irrepressible gutsiness. Yet now I loved even more the Pauline Kael I saw at the end of her life: a woman who had always liked to give more than she received, but who now needed help from her friends. And then she was gone.

What makes someone’s personality remain vividly alive in our hearts and mind even when they're no longer with us? Our personalities are something many of us wrestle with. We go to shrinks to get over our flaws and neuroses. We try to model ourselves after bosses, celebrities, artistic idols -- people we think are better than we are. We can think that who we are is keeping us from who we want to be, or even a wall between us and the rest of the world. What Pauline realized is how valuable our individuality is. How the various components that make us uniquely ourselves can be the very thing that connects us to others, to the world. She showed us how filtering what we’ve experienced through our personalities can illuminate the world for others -- how our personalities can be the basis for great art.

Pauline taught me that in the end it’s all in how you play yourself.

***

Further reading:

I Lost it at the Movies by Pauline Kael

The Age of Movies: Selected Writings of Pauline Kael

Pauline Kael: A Life in the Dark by Brian Kellow